Bruce Hornsby is writing a Broadway musical.

“Do you know who Brian Stokes Mitchell is?” he asked me when I visited him earlier this month. “He’s a Broadway actor, not so well known outside of the Great White Way, but he’s a big deal on Broadway. He was a big fan of my last record; there’s a little three song area that is sort of solo piano—‘Hooray for Tom,’ ‘What the Hell Happened’ and ‘Heir Gordon.’ He thought it sounded like Broadway, and he thought that I should be writing a Broadway musical.”

We were talking in the recording studio at his home in Williamsburg the day after the 4th of July. He would fly out to Colorado the next morning to begin a three-week western swing with his band. After sitting at his Steinway and playing me a humorous new song written for the musical with childhood friend Chip DiMatteo, he played some rough mixes from an upcoming jazz album recorded this spring with bassist Christian McBride and legendary drummer Jack DeJohnnette.

“I’ve never been busier on a recording level,” he said. “I’ve certainly been busier on a touring and performance level—before my wife and I had our sons…to be perfectly honest with you, we were building this place and I wanted it to not be difficult. So I busted my ass hard. In 1990, I was home for eighteen days; I was gone 347 days. Then the next year, 1991, I was gone all but thirty days.

“I’ve never been busier on a recording level,” he said. “I’ve certainly been busier on a touring and performance level—before my wife and I had our sons…to be perfectly honest with you, we were building this place and I wanted it to not be difficult. So I busted my ass hard. In 1990, I was home for eighteen days; I was gone 347 days. Then the next year, 1991, I was gone all but thirty days.

“This was the time I was playing with two bands, my band and the [Grateful] Dead. I was playing on tons of records, producing Leon Russell, writing with Robbie Robertson. I was getting all these great calls; it was hard to turn ‘em down. I [also] got a lot of calls from people who no one had ever heard of, new artists. I think people started realizing that I was a cheap date.

“Consequently a lot of things I did were not enjoyable. I would get to a session and try to play something that I thought was unique, interesting and different. And almost invariably the producer would say, ‘That’s very interesting, but can you simplify it or just play it a little more straight.’ And inevitably in the end, what I ended up doing for them sounded so generic to me, I would say, ‘You know you could’ve gotten anybody to do that.’

“I started saying no to most things once the boys were born because I wanted to try to find a balance between having an intense career and not being the absentee dad.”

Has he succeeded?

“You’ll have to ask them when they’re grown!” he laughed. “They’re fourteen now. One of them is really into flying—he flies gliders solo over in Isle of Wight. And the other one’s into basketball. He’s on the AAU state champion Boo Williams select team, the only white kid in the gym. He’s going to the nationals in Orlando in August. He can really shoot it, and he’s a quick little white boy. He’s way better than me.”

-

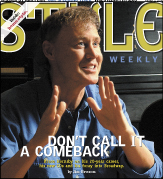

It’s been twenty years since Bruce Hornsby set the music world on its ear with his first album, The Way It Is. The title track to that album hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100 on December 13, 1986. Two months later Bruce Hornsby and the Range were at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles accepting the Grammy Award as Best New Artist. It looked like an overnight success story, but in reality it was anything but.

“It’s all about our path,” he began. “Our road into the music business started with my drummer John Molo and myself going over to the Sheraton Coliseum looking for Michael McDonald of the Doobie Brothers, because they were playing at Hampton Coliseum. Sure enough, we found him in the lobby, getting ready to go to a movie. We went up to him [and] said, ‘Hey Mike, we’re the baddest mothers in this town, and we’re playing right over here at the Jolly Ox and you should come hear us.’

“It’s all about our path,” he began. “Our road into the music business started with my drummer John Molo and myself going over to the Sheraton Coliseum looking for Michael McDonald of the Doobie Brothers, because they were playing at Hampton Coliseum. Sure enough, we found him in the lobby, getting ready to go to a movie. We went up to him [and] said, ‘Hey Mike, we’re the baddest mothers in this town, and we’re playing right over here at the Jolly Ox and you should come hear us.’

“Michael McDonald is a great person—I call him my discoverer and founder. He said, ‘I’m going to this movie; I’ll try and come later.’ And sure enough he did, and we’d saved all of our originals to play a set for him. There were about fifteen people in the bar, pretty empty. And so we were just hitting it, doing as well as we could do. And he was really into it. He said, ‘Come back to the hotel; let’s hang out.’ So we went back to the Sheraton.

“The next night they played a concert at Hampton Coliseum; Ambrosia was the opening act. He told me that afternoon, ‘After the concert, I’m gonna bring everybody over.’

“It took them forever. We must’ve taken an hour and fifteen minute break waiting for them to come. The club owner was getting pissed but the word had gotten out; the place was packed. I get chills thinking about it now—one of those amazing life-changing moments. They all came, we played our set, Mike even sat in with us.

“About two months later we went to Alpha Audio in Richmond and made a very half-assed demo. We sent him the tape—I think he was a little underwhelmed!

“But anyway, Molo and I went out and slept on his floor for ten nights in February [1979]. A couple of producers got interested in our tape. One of them was Jeff Baxter, who was leaving the Doobie Brothers, and also Mike Post, the big TV writer—Hill Street Blues, Magnum P.I., L. A. Law. Of course we went with Baxter because we thought, wow…a cool cat! So we went to his house and he said, ‘OK guys, let’s get high and make a record.’ That was his opening line.”

A month of showcase performances in Hollywood led to one small label offer which they chose not to take. Everyone else said “no thanks.” Nonetheless, Hornsby’s songwriting attracted the attention of industry honchos.

“I got all these publishing offers for the very same reason we got passed on: They thought we sounded too much like the Doobie Brothers. Artistically it was derivative, but for a publisher that was sort of in vogue. So I ended up signing with David Foster and 20th Century Music as a writer.”

-

He and Molo moved out to Los Angeles in April, 1980, with guitarist Steve Watson. His future wife Kathy joined him there that summer. Success appeared to be just around the corner, but the dues paying had only just begun.

“I was ‘bubbling under’ for a lot of years,” he recalled. “I spent seven years basically getting turned down; I probably got passed on seventy or eighty times by the record companies. Every year I would make a new demo of songs, and they were interested enough in me, they thought I was talented enough, that they would always listen.”

But the big break didn’t come. Promises and encouraging words from industry bigwigs like Foster, David Geffen, Lenny Waronker and Huey Lewis led only to dashed hopes.

“About 1983, I started to move away from the Steely Dan and Mike McDonald kind of music, and more into Tom Petty and Springsteen, American roots rock, and getting back into the groups I was into in high school like The Band and Dylan. My music started moving more into that Americana, roots influenced music.

“We started this band in ’84, The Range. I thought Bruce Hornsby was a terrible stage name; we were just called it The Range. It felt American, it felt open, it felt like the music I was making. We had songs like ‘The Wild Frontier,’ ‘On the Western Skyline,’ ‘Red Plains.’ I didn’t play piano, I was playing accordion.

“We dressed up in period garb; it was my one effort to play the game, but at least I wasn’t getting a new wave haircut and wearing a skinny tie. We were just sort of dressing up in old suits from the ‘30s, that type of thing. I guess you could say we looked more like a bluegrass band; not with hats and ties, mind you, but just those kinds of pants and nice shirts.”

Another demo failed to garner any record company interest:

“It became embarrassing to me because I had all these great people trying to help me and I couldn’t get arrested.”

He began to question the quality of his songs. He couldn’t get the sound he was looking for with his band, so he decided to take matters into his own hands.

“After our final big attempt didn’t work, it’s ’84, I’m turning 30 years old. So I said, well screw this…I’m going to record this just once with everything on the tape being out of my head. So I cut a couple of songs with drum machine, piano, synth bass, a little keyboard pad…and vocals. Simple.”

William Ackerman at Windham Hill Records liked what he heard and offered a recording contract. But Hornsby’s attorney advised against accepting the small label deal, and played the tape for friends at some of the larger record companies. RCA and Epic both wanted him.

“They didn’t think it was commercial. They just couldn’t stop listening to it. It moved them. So it’s a very simple scenario in theory. How do you get a record deal? You make a tape that moves the people that have the power. It’s simple in theory but it’s very hard to do.

“The moral of this story is, after all the years I spent trying to fit into some notion of what was happening, it was when I turned my back on it and made the least commercial tape that I’d ever made, that’s when they embraced me.”

The Way It Is was recorded in 1985 and released in the spring of 1986. But it wasn’t until a BBC disc jockey played the title track, one of those original self-produced demos, that the album and the song took off.

“Our record was not an instant success,” he said. “The least commercial song on the least commercial tape was ‘The Way It Is.’ Everybody thought it was a B-side.

“You’d have to give credit to the BBC Radio One disc jockey, Mik Wilkojc. He picked this one song, put it on the air—Boom! It exploded. We got these faxes: ‘The Way It Is’ is exploding in England, then in Holland. By the time they put it out over here, it was number one in Holland, top ten all around the world. The United States was late to the party.”

-

Home is important to Bruce Hornsby. After spending the ‘80s grinding through the gears of the star making machinery in LA, he and Kathy moved back to Williamsburg in 1990. Older brother Bobby, his musical partner from childhood into young adulthood, built them a beautiful home and studio. He had returned to his hometown, to a region filled with relatives:

Home is important to Bruce Hornsby. After spending the ‘80s grinding through the gears of the star making machinery in LA, he and Kathy moved back to Williamsburg in 1990. Older brother Bobby, his musical partner from childhood into young adulthood, built them a beautiful home and studio. He had returned to his hometown, to a region filled with relatives:

“Old J. W. Hornsby, who died in the early ‘50s, was a waterman until he got an oyster tong through his foot one day and said the hell with this, and told his brother Red Hornsby to take him to Yorktown where he decided to get into the heating oil business. I don’t know how he got into it, but he started Hornsby Heating Oil and that was the family business. My dad went off from that and became a real estate developer before that was a four-letter word. He played sax in his brother’s band, Sherwood Hornsby and the Rhythm Boys.

“I had great parents. The romantic story is the terrible childhood, you know, scuffling and turmoil at home. That’s a beautiful romantic story; it’s not my story. I had a great childhood with great parents. And I guess confidence was instilled in me.”

Music flowed through the family genes:

“My mom’s father was a musician in Richmond. He was the Mosque organist. If you’d go to the state Jaycees convention, he was the guy playing ‘Turkey in the Straw’ over in the corner. He was the supervisor of music in the Richmond public schools—Paul Saunier was his name. It was a very musical family. They have tapes of me singing ‘Hound Dog’ at age three or four, my brother singing Ricky Nelson, my younger brother singing ‘Charlie Brown.’

“I took lessons at age seven for about a year and a half and bagged it. I wanted to be outside playing sports; I was a real jock as a kid—football, basketball, baseball. Bobby was the first one to get serious about music. We both sang with ‘Up with People’ when we were little kids. My mom got us into it; she was really into all of that. We were in ‘Sing Out Williamsburg.’

“I was little Brucie Hornsby writing these songs at age twelve, thirteen and playing guitar. I didn’t start playing piano ‘til I was seventeen other than that one year. Bobby showed me some chords early on, and I could play a few soul tunes. But he was the one who was really serious about music. He had a soul band called The Soul Solution and a psychedelic band called Love Minus Zero. So he was really more the music guy and I was more the jock, but it always came pretty easily to me. Like him I had ears, so I could hear a song and play it.

“My mom was the fearless one in a social sense. Early on, she was very pro-civil rights, and that was not a popular stance around here.”

The family lived on Indian Springs Road, across Jamestown Road from Phi Beta Kappa Hall. As a townie in a touristy college town, he enjoyed harassing preppy William & Mary students.

“We useta throw water balloons at them,” he laughed. “We would only pelt guys who were really dressed up nice with their dates. We would just blast those guys.

“One of them, a law student named Walter Meisner, flagged some cops down and followed us. And they took us down to the police station, about six of us in a car having a ball. Our parents had to go in, and my dad was just classic—this guy was saying ‘your kids are terrible, total hooligans, and they should be punished.’ And some of the mothers were just, ‘you’re right, I can’t believe that my son…’ And my dad finally said, ‘You know what? Enough of this! They did this, they shouldn’t have done it, but it’s not that damn big a deal. I’ve heard about enough out of you and I’m done, I’m outta here.’ And this guy was totally taken aback.”

-

Much of the Hornsby lyrical canon comes from true stories, things he did, people he knew, stories he’s heard of goings on in his hometown.

“I always thought I would come back,” he said. “Lyrically, I wanted my music to have a strong sense of place, so I always wrote about this area. I thought if I came back here I might become more prolific, and I was. ‘White Wheeled Limousine,’ the song about the guy who gets caught in the bushes with another woman on the day of his wedding—that actually happened. In the song, she finds out about it and it breaks up. But in reality, they actually got married; she never found out.

“[‘Sneaking Up On Boo Radley’] is a combination, obviously, of Harper Lee and the fact that we grew up here with Eastern State Hospital where there were patients walking around town all the time that we would make fun of. We knew a lot of them. My mom, liberal Lois Hornsby, ‘all are welcome,’ we had a lot of patients come to our house. They would hang out…there’d be a knock on the door, and there’s Welford Thurston looking for a handout.

“Race and religion, that’s such a rich area. I’ve always been influenced by southern writers. Lee Smith, I love her writing. I always loved William Styron; Sophie’s Choice is one of my favorite books, hilarious and horrific at the same time. I always wanted my songs to reflect that same feeling.”

This week, RCA Legacy is releasing a 4 CD/1 DVD box set called Intersections (1985-2005). It’s an impressive summary of Bruce Hornsby’s musical career. But it is hardly a traditional “greatest hits” collection. In fact, most of the old songs are presented in new, expanded live versions, some solo, some with the current band.

This week, RCA Legacy is releasing a 4 CD/1 DVD box set called Intersections (1985-2005). It’s an impressive summary of Bruce Hornsby’s musical career. But it is hardly a traditional “greatest hits” collection. In fact, most of the old songs are presented in new, expanded live versions, some solo, some with the current band.

“It has to do with our approach,” he explained. “Most people approach their songs like museum pieces: ‘this is the way we recorded it, and it’s the way we’re going to play it for the rest of our lives.’ I think of our songs as living beings that grow and evolve. So the box set is not meant to be a retrospective, it’s an artistic statement in the present. This is what I’ve become.

“Some of the old records, I find them unlistenable, mostly on the vocal level. I feel that through the years I’ve just loosened up so much, it’s miles beyond to me. I wanted a document that existed so that if someone didn’t know what I did, I could say, ‘here, this is what I do.’ Where else would you have a duet with Ornette Coleman, a song with the Grateful Dead and a couple of bluegrass records, jazz tunes with Mardi Gras horns and Branford Marsalis, and Spike Lee movie songs. It’s such a broad range, it’s the only way you could have it in one place.

“Within this box set is pretty much an album’s worth of solo piano back-to-back in order. So, here’s my document; this is what I’m about. There’s already a ‘greatest hits’ record out there. But this is an artistic statement about what I really do.”

It’s a powerful personal statement, one of the best, most adventurous box sets ever put together by a popular musician. Unlike some performers, Bruce Hornsby has continued to grow as an artist, to expand his horizons. He has refused to fit into any formula, yet he has built a fan base that keeps coming to hear what he’s up to, willing to follow wherever his muse leads.

“We had all those hits,” he said, “six, from ’86 to ’90; and then the songs I wrote for other people that were big hits—“Jacob’s Ladder” for Huey Lewis and with Don Henley, “The End of the Innocence.” So we had a real strong presence for a good five years on the radio. But I started getting these calls to work with other people. I was inspired by all this. So I broke up The Range ‘cause I wanted to have the freedom to cast my own sonic film.

“That was the end of my radio run because I didn’t want to be tied to always having to fit that mold…If I’d continued to play it safe, or play it the way most people do, I don’t think I’d have an audience now.

“My musical life since that hit period has been about the pursuit of musicality and finding new ways to be inspired, just trying to be creative.”

Over the years, Hornsby has honed his piano style, creating a unique sound that combines the free flowing jazz sensibilities of Keith Jarrett and McCoy Tyner with the folksy Americana of composers Aaron Copland and Charles Ives. In fact, Ives is the American composer who first captured Hornsby’s interest, and still does. He played me an Ives etude that he adapted for his new jazz album that was remarkably complex in its seeming abandon.

“I liked Ives in college, Berklee College of Music,” he said. “The best part about Berklee to me was the town. Boston was an amazing artistic resource. They had two jazz clubs, the Jazz Workshop and Paul’s Mall right on Boylston Street side by side. At the Boston Public Library you could check out records. I got into all this music that I now play.

“I almost got sued by the Ives people. ‘Every Little Kiss,’ the piano intro is virtually a paraphrase of the Concord Sonata, the third movement. They said, ‘You’ve stolen our song.’ And my reply was, ‘Yes, you’re right. It was an homage, and that’s exactly right.’ They were so amazed that I said ‘yes’ that they said ‘OK, forget it.’”

-

Bruce Hornsby seems to be hardwired for happiness. Remember seeing his big smile playing the piano behind friends like Don Henley and Bonnie Raitt on televised award shows in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s? Or watching him walk out onstage locally with Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan or Crosby, Stills & Nash?

In person, he is the epitome of optimism, excited not only about his own projects, but also interested in the person he’s talking with. He loves to discuss music, and has stayed plugged in to contemporary trends.

“There’s something I like about it,” he said of rap and hip-hop. “The minimalist aspect—there’s no harmony. It’s not what I’m about, but I like it. The most clever hip-hop is incredible lyrically. It’s really happening.”

When he discovered that I had once gone to New York hoping to become the next Dylan, he lit up.

“I thought of you as more of a jazz guy!” he said excitedly. “So you’re a Dylan man…I was big into Dylan. ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ was the first record that I could sing along and phrase every phrase along with, mimicking. I played that little 45 over and over again, six minutes long, the red Columbia label. When I signed with Columbia and made Halcyon Days, they sent me this CD artwork with a nice picture of me playing. And I said, ‘no, no, just give me the old red label.’”

Having his name on that red Columbia label is just one of the many dreams that have come true. He has a room in his house filled with awards, gold and platinum records, pictures and mementos that he calls his “ego room.” The walls and bookcases are filled to the ceiling. There’s literally no space left for any more honors.

But there will surely be more to come. It’s clear that in his 52nd year, he is still finding new inspiration, still generating creative sparks. Besides the box set and the Broadway musical, he has two other CDs coming out this year—the smokin’ jazz trio disc and a bluegrass album with Ricky Skaggs. In many ways, he feels like he’s bringing his musical career full circle from the old days playing in local bands:

“For someone who ran into me down at the Pungo Bluegrass Festival in Virginia Beach in 1974, fast forward thirty two years later and now I’ve painted myself into that mural full-force—I finally made a record of that music, because I always loved it then. To anyone who was at the Jolly Ox, Janaf Shopping Center seeing us play ‘Twelve Tone Tune’ by Bill Evans when everyone hated it and we got fired, then fast forward twenty nine years later and here I’m finally making this jazz record.

“For anyone who went to Hampton Roads Academy in 1973 and saw our musical play, ‘Schenectady’ and the sequel ‘Son of Schenectady,’ fast forward all these years and we’re trying to write this play, we’re trying to do this on a higher level.

“Everything I’m doing now, there are seeds that were planted years ago around here.”

--photos by Kathy Keeney--

copyright © 2006 Jim Newsom. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

“I’ve never been busier on a recording level,” he said. “I’ve certainly been busier on a touring and performance level—before my wife and I had our sons…to be perfectly honest with you, we were building this place and I wanted it to not be difficult. So I busted my ass hard. In 1990, I was home for eighteen days; I was gone 347 days. Then the next year, 1991, I was gone all but thirty days.

“I’ve never been busier on a recording level,” he said. “I’ve certainly been busier on a touring and performance level—before my wife and I had our sons…to be perfectly honest with you, we were building this place and I wanted it to not be difficult. So I busted my ass hard. In 1990, I was home for eighteen days; I was gone 347 days. Then the next year, 1991, I was gone all but thirty days.  “It’s all about our path,” he began. “Our road into the music business started with my drummer John Molo and myself going over to the Sheraton Coliseum looking for Michael McDonald of the Doobie Brothers, because they were playing at Hampton Coliseum. Sure enough, we found him in the lobby, getting ready to go to a movie. We went up to him [and] said, ‘Hey Mike, we’re the baddest mothers in this town, and we’re playing right over here at the Jolly Ox and you should come hear us.’

“It’s all about our path,” he began. “Our road into the music business started with my drummer John Molo and myself going over to the Sheraton Coliseum looking for Michael McDonald of the Doobie Brothers, because they were playing at Hampton Coliseum. Sure enough, we found him in the lobby, getting ready to go to a movie. We went up to him [and] said, ‘Hey Mike, we’re the baddest mothers in this town, and we’re playing right over here at the Jolly Ox and you should come hear us.’

Home is important to Bruce Hornsby. After spending the ‘80s grinding through the gears of the star making machinery in LA, he and Kathy moved back to Williamsburg in 1990. Older brother Bobby, his musical partner from childhood into young adulthood, built them a beautiful home and studio. He had returned to his hometown, to a region filled with relatives:

Home is important to Bruce Hornsby. After spending the ‘80s grinding through the gears of the star making machinery in LA, he and Kathy moved back to Williamsburg in 1990. Older brother Bobby, his musical partner from childhood into young adulthood, built them a beautiful home and studio. He had returned to his hometown, to a region filled with relatives:  This week, RCA Legacy is releasing a 4 CD/1 DVD box set called Intersections (1985-2005). It’s an impressive summary of Bruce Hornsby’s musical career. But it is hardly a traditional “greatest hits” collection. In fact, most of the old songs are presented in new, expanded live versions, some solo, some with the current band.

This week, RCA Legacy is releasing a 4 CD/1 DVD box set called Intersections (1985-2005). It’s an impressive summary of Bruce Hornsby’s musical career. But it is hardly a traditional “greatest hits” collection. In fact, most of the old songs are presented in new, expanded live versions, some solo, some with the current band.