Long before Jeff Foxworthy legitimized being a redneck, a decade before Hee Haw took cornpone mainstream and just about the time Andy Griffith first strode into the Mayberry sheriff’s office, Brother Dave Gardner was taking southern comedy up the record charts and onto late night TV. His first two albums hit the Billboard Top 10 in the summer of 1960 and he was a frequent guest on Jack Paar’s Tonight Show.

At the time, David Anthony Wright was growing up in Burlington, NC. There was something about Brother Dave that connected with the youngster.

“I started listening to his albums when I was thirteen,” he told me a couple of weeks ago. “I didn’t get all the references at that age, but I knew that if this guy could make people laugh that long, that loud—and obviously enjoy it as much as he did—he had to be something really special. I memorized all his bits just as people a little later memorized Bill Cosby or Richard Pryor or the Smothers Brothers.”

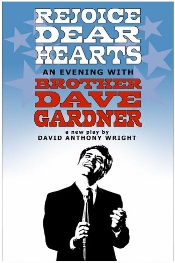

Wright had no idea that more than 40 years later, he’d be responsible for resurrecting his boyhood idol’s routines and introducing him to an audience that had long forgotten or had never heard of him in the first place. But that’s just what he’s doing with his one-man play, Rejoice Dear Hearts: An Evening with Brother Dave Gardner, coming to the American Theatre Saturday night.

Wright had no idea that more than 40 years later, he’d be responsible for resurrecting his boyhood idol’s routines and introducing him to an audience that had long forgotten or had never heard of him in the first place. But that’s just what he’s doing with his one-man play, Rejoice Dear Hearts: An Evening with Brother Dave Gardner, coming to the American Theatre Saturday night.

“Prior to Dave Gardner,” he said, “most of your southern comedians were gap-toothed, funny hat, baggy pants hayseed types. Here comes Dave out of Jackson, Tennessee, and his comedy was firmly rooted south of the Mason-Dixon line, but he was southern hip, southern cool. This was a guy who could tell stories in the classic southern style and at the same time do these amazing stream of consciousness, what you’d call today ‘rants.’

“He was like Red Skelton—you knew he was having at least as much fun as the audience. He had this rapport with the audience, this infectious laugh that just caught people’s imagination.”

David Anthony Wright got the opportunity to create his memento when he came home to Burlington after a career in broadcasting:

“I’m managing the theatre here that was my boyhood haunt when it was a first-run movie house. The city renovated it back in 1998 and turned it into a performing arts/multi-purpose center. That got me out of a 29-year sentence in the radio business. You name it I did it at enough radio stations where I covered every letter of the alphabet except two!

“On Valentine’s Day of 2002, my nearly-perfect wife Susan gave me a copy of Brother Dave’s Rejoice Dear Hearts! album. She knew that I had been a Brother Dave fan when I was in my teens and, depending on the format I was working, I would be either ‘Brother Dave’ or ‘Doctor Dave.’ Brother Dave-isms had been in my vocabulary; if something good happened, it was, ‘Oh, rejoice!’ It was just a natural part of my persona. But I hadn’t listened to any of his albums in years.

“So Susan gives me this album and I listened to it all the way through before breakfast, and all those memories came flooding back. So I go on the internet and read his obituary and, just based on that, I walked into the breakfast room and said, ‘There’s a play in this man’s life, and I’m gonna write it and I’m gonna do it.’ Three days later I was able to track down Dave’s daughter, Candace Hare, and found her living just outside of Ft. Worth, Texas. I called her and told her, ‘I want to do a play about your daddy.’

“The silence on the other end of the line was deafening.”

Candace and her husband were less than enthusiastic because they’d been burned before by performers trying to capitalize on her father’s material. But Wright was both patient and persistent, and ten months later he had their blessing to begin writing his play. (“At that point, they began to flood me with stuff; it was an absolute gold mine.”) The premiere in August, 2004, at Wright’s Paramount Theatre in Burlington was a huge success, selling out all three nights and drawing people from nine states.

Rejoice Dear Hearts is filled with Brother Dave Gardner’s jokes and comedy routines, but it also tells the story of his life. It was a life filled with triumph and tragedy.

“It’s the classic rags-to-riches-to-rags-to-redemption story,” Wright said. “He had four million-selling albums and helped launch the comedy album craze. [But] they recorded an album of Kennedy material that was set to be released in January, 1964. Of course we all know what happened in November.”

He also was busted for marijuana possession, and was seriously injured along with his wife and daughter in a 1966 plane crash. A few years later, he got into trouble with the IRS.

“Dave had always been conservative in his politics,” Wright explained, “and he came under the spell of H. L. Hunt. Hunt actually convinced them that the Internal Revenue Service laws were unconstitutional. So they quit paying taxes for three years, hoping to be a test case. They were sure that Hunt would back them up and help with their legal bills. The IRS just jumped on them for three years of unpaid taxes. He thought he’d be on the cover of Time magazine for taking on the IRS; they ended up losing everything they had and Hunt ran like a rabbit.

“For about the next five years—they finally settled in 1975—nobody would touch ‘em. They were in near-poverty.”

Gardner died in 1983 in the early stages of what looked like a possible comeback. But even after his death, he remained little more than a faded memory, virtually unknown to the generations born after his brief heyday in the early ‘60s. Still, his place in the comedic history books is undeniable.

“He proved there was a market for comedy in the recording business,” Wright said. “That paved the way for everybody who came after. He proved that you could be funny without being hurtful. And I think he showed another side of the south—that there was an intelligence, a literary background, in the south. And in the process he could make you double over with laughter.

“The guys who are out on the road now—I hope they’re aware of Dave’s influence. It would be a lot tougher for them to be out doing all the stuff they’re doing if Dave Gardner had not blazed the trail.”

copyright © 2006 Port Folio Weekly. Used by Permission.