The Byrds

There is a Season

Columbia/Legacy

“That’s Naw-fk, isn’t it?” Chris Hillman laughed last month when I called him at his office in California. “I’ve played there a lot and I’ve had many good times there. It’s one of the perks of touring for forty-four years—sometimes you get the regional dialects.”

The reason for my call was the new Byrds box set hitting record stores this week, There is a Season. Featuring 99 songs on four CDs and a DVD with ten television performances from the ‘60s, it’s a superb collection. But, there is already an excellent four-disc, 90-song set released in 1990 that most Byrdmaniacs have, and the band’s entire catalog has been issued in expanded editions. So I wondered what the impetus was for this new release.

“The last one was pretty good,” he said. “I think they could’ve had more Gene Clark material included. And the artwork on each CD looked like something you’d see at a massage studio; it looked like new age music. But the box was great, the black box. I don’t know what this box looks like, but I like the booklet, I like the DVD. I like the material, but I still have to stick with The Byrds were the original five guys; the newer stuff, with all due respect to McGuinn and Clarence White, it doesn’t hold up to me personally. That’s subjective, but to me, that live stuff is a little weaker than I would’ve put in this current set. But I don’t know if I should tell you that!”

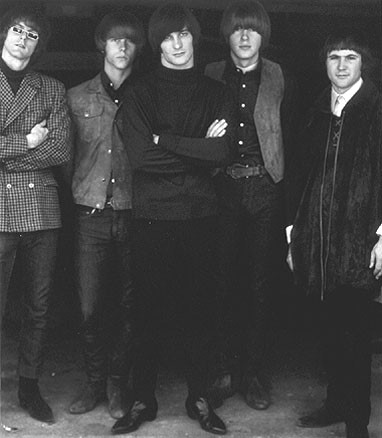

If anyone is qualified to comment on the musical development and history of The Byrds, it’s Chris Hillman. He was the band’s original bass player, a baby-faced nineteen year old when the band formed in 1964, who stood in the back next to drummer Michael Clarke while the frontline of Roger (or Jim, as he was called in those days) McGuinn, Gene Clark and David Crosby blended their voices together in those trademark harmonies. But when he joined, he didn’t actually play bass.

“The guy who was initially recording the three,” Hillman remembered, “I had worked with in my bluegrass band. We had two names—the Golden State Boys and the Blue Diamond Boys. Jim Dickson had recorded us, and he thought I would fit in real well with this bunch of guys. And after I heard ‘em sing, I thought they were really good.

“When they asked me to be the bass player, I just sort of played the hand and went, ‘Yeh, I can play bass.’ I didn’t know how to play bass, but I realized they didn’t know how to play electric guitars either. So we all were just plugging in and we didn’t have a blueprint. We did not have a game plan. The uniqueness of The Byrds is that we didn’t know what the hell we were doing and off we went, drawing on our past experiences in acoustic music. The other guys were coming from a more commercial, Kingston Trio-type folk music deal. I came right out of hillbilly bars. I had a fake ID; I was working in some places you would not even walk in to, where you played bluegrass every weekend. One of the clubs we worked in was called the Harem Lounge—you had working class white guys in there beating each other up.

“The other guys were coming out of folk clubs. Roger McGuinn and David Crosby were very seasoned—they’d been around the country, Roger being the most seasoned of all of us. We just, by trial and error, developed a sound around McGuinn’s twelve-string. Basically he was playing the same thing he played as an acoustic accompanist to The Limelighters and Bobby Darin and the Chad Mitchell Trio; he just happened to plug in his Rickenbacker and we worked around that particular style of guitar playing. But it was a great sound. I was a lucky kid, and I figured out the bass around the end of the first record or the beginning of the second.”

Rumors have long circulated that The Byrds didn’t actually play the instruments on their magnificent first album, Mr. Tambourine Man. But Hillman is quick to debunk that myth:

“A lot of bands in those days, with the exception of The Beatles, didn’t play on their own records. But “Tambourine Man” was the only song the band didn’t play on. Columbia Records was sort of hedging their bets, ‘we’re giving these guys a singles deal;’ meaning that if the single takes off, we have the option to do an album. We played on everything else; in fact I will go on record saying we were better in the studio than we were on stage. We took sort of a lackadaisical attitude onstage but in the studio we made pretty darn good records.”

That they did. “Mr. Tambourine Man” was number one on the Billboard Top 40 the week of June 26, 1965, and The Byrds were proclaimed as “the American Beatles.”

“Initially, of course,” Hillman acknowledged, “we wanted to be like The Beatles until Jim Dickson steered us away from that and pounded it into our heads to go for substance over style, go for depth in the material. Here’s a song—Bob Dylan, ‘Mr. Tambourine Man,’ it hasn’t been put on a record, Bob just wrote it—listen to this. And everybody was a little wary of it. But McGuinn, with all due respect, put that arrangement to it.

“So our manager steered us out of emulating The Beatles and trying to be some sort of second rate American Beatle band with clothing, hair and all of the accoutrements, and put us more into our own thing. It took a while, but once we started to get clear of the Bob Dylan covers, we started to develop our own style of music. We got songs like ‘Eight Miles High,’ but the best known of our songs is probably ‘Turn Turn Turn’ which is out of the Old Testament, written by King Solomon with music by Pete Seeger.”

The Byrds were one of the most adventurous bands of a very adventurous era, helping to invent folk-rock, venturing into early psychedelia, incorporating free form jazz elements and pioneering country-rock. It’s all captured on There is a Season, remastered and sounding better than ever. And the DVD is a lot of fun, too, but all the performances are lip-synched.

“Unfortunately,” he explained, “that’s the way it was back then. The Ed Sullivan Show you did live and The Tonight Show, but they’re not on there; otherwise everything you did was lip-synched. But I love watching the go-go dancers—Hullaballoo or Shindig.”

Chris Hillman went on to an enviable career in music after leaving The Byrds in 1968—he was a founder of the Flying Burrito Brothers, Stephen Stills’ Manassas, Souther-Hillman-Furay Band and a 1980s country superstar with his own Desert Rose Band. But it’s his tenure as a founding member of The Byrds that got him enshrined in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and is his lasting legacy.

“I’ll always be remembered as one of The Byrds,” he said, “even if I was just the bass player. We left a helluva legacy for people to follow, vocally and instrumentally. For a bunch of five of the weirdest guys from the most diverse backgrounds, it worked! In the early days it was like all five of us were each holding a paintbrush and all trying to paint the Mona Lisa’s smile. And we made it happen.”

copyright © 2006 Jim Newsom. All Rights Reserved.