How do you make a living playing music?

“Rule number one is marry well,” Stephen Bennett says with a smile in his voice. “I wound up being a musician with health insurance. My wife’s on the faculty at William & Mary, which doesn’t hurt a bit.”

We are talking by phone on a day when the winds are wailing and snow is blowing blizzard-like down the street outside my window in downtown Norfolk. Bennett has a combination snowstorm/thunderstorm swirling around his home in Gloucester County. He’s been playing guitar for more than thirty five years and working as a full-time musician since 1982. Saturday night he’ll perform in the new Kaufman Theatre at the Chrysler Museum with some musical friends in a boundary-crossing acoustic group called Orpheus.

“It’s a quartet right now,” he says of Orpheus. “It’s myself and my brother Jim, who’s a wonderful piano player from Richmond; Jimmy Masters, who’s a wonderful bass player; and my friend Bill Gurley, who’s more out of the folk tradition, who plays fiddle, banjo, guitar and mandolin, and sings a bit. It’s a chance to play some music that I don’t get to play in a solo setting, and to work with some guys that I like to play with and I like as people. And we can occasionally make some magic.”

Stephen Bennett began learning to make musical magic when he was growing up in the Hudson River Valley near West Point, New York:

“When I was twelve years old, 1968, the pop music that you heard at that time was wonderful, and I just fell in love with it right away. There was a guitar sitting around the house and I picked it up. In the back of one of the books that was in the house---Mel Bay or Hal Leonard or something like that---I didn’t pay any attention whatsoever to the rest of the book, but there was a page of chord diagrams. And you learn really quickly that once you have memorized even just a half dozen chords and you can move from one to the other, all of a sudden you are making music. You may not be terribly good, but you are making music. It sounds good, it’s fun, you want to play more, you get better…and it’s a nice cycle that starts.”

He followed a path typical for aspiring guitarists of his generation, playing in rock bands and soaking up everything he heard, constantly working to improve his skills and develop a voice of his own.

“I loved The Beatles,” he remembers. “I was a huge Yes fan---I still love Steve Howe. I guess I heard Leo Kottke the night I moved away to college. That was kind of a life-changing experience and I went through a Leo Kottke phase for a while. What a groundbreaking sound that was.

“I went through a Doc Watson phase. And there was a guitar player in Boston named Guy Van Duser---I never really had a Chet Atkins phase, but because I had a Guy Van Duser phase, I, in fact, had sort of a second hand Chet Atkins influence because he was so heavily influenced by Chet.”

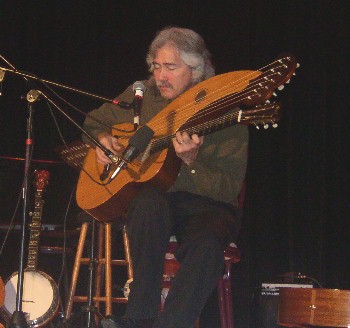

And he got better and better, winning the National Flatpicking Championship in Winfield, Kansas in 1987. Around the same time, he began playing the instrument with which he has become most identified and most often photographed, the harp guitar.

“I came across the harp guitar in the late ‘80s,” he explains. “I inherited it, basically, from my great grandfather.”

“I came across the harp guitar in the late ‘80s,” he explains. “I inherited it, basically, from my great grandfather.”

It’s an instrument that looks like a hybrid from another world, with a regular six-string guitar on the bottom and an extended harp-looking six-string thing sticking out of the top left quadrant where the neck connects to the body of the guitar.

“What you wind up with is this funny looking thing that’s very photogenic,” he says by way of description. “You wind up with something a little more pianistic than a regular guitar. It’s not like I have a bass player all of a sudden along with the regular guitar, although they are in fact bass strings. I don’t really approach it that way. I just approach it as a guitar-plus. It’s a guitar with a little extra range in the lower end. And just by hitting an occasional note down there you can add so much because you’ll be freed up on the regular guitar. That bass note will sustain underneath you.

“The other quality of the instrument is that, aside from the extra notes you have, all those extra bass strings act like the sustain pedal of a piano, so they are ringing with sympathetic vibrations all the time. So just like with a piano, how you have to work the sustain pedal---otherwise everything will just turn into mush---a part of learning how to play the harp guitar is learning how to continually dampen the strings. I don’t even think about it, it’s just I’m constantly doing it. I’m also playing the bass notes, but as I say, I’m not thinking of it as a bass player.”

Stephen Bennett has been a Virginian since 1977, when his wife-to-be came to graduate school at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. He currently travels throughout the country and around the world playing his unique brand of music, mostly in solo settings. Upcoming travels include trips to New Hampshire, Michigan, Tennessee and Kansas, as well as a guitar festival in Soave, Italy.

“It’s a niche kind of following,” he says. “The kind of music that I play is the sort of music that, if people actually hear it, there are many more people who would enjoy it than know about it. They haven’t been exposed to it.

“NPR is really the only place that I get radio airplay and I have gotten that for fifteen years now. All Things Considered uses me for segues. You can catch me pretty regularly, there’s about a fifteen second clip on Weekend Edition Saturday.”

He’ll have his full arsenal of guitars this weekend at the Chrysler Museum:

“I always have my regular six-string, a 1930 National Steel that I play slide on, and a harp guitar. I fly with those all over the world. And I’ll add to those a baritone guitar, a high-strung guitar, and a twelve-string sometimes. For the Orpheus thing, I’ll have all those guitars.”

Stephen Bennett is a genuine musical treasure right here in our midst, one of the most highly respected giants of contemporary acoustic guitar. And he feels very fortunate to be able to make music for a living.

“I guess if you can remain standing long enough, you can actually emerge standing at the other end of it. One day you realize, ‘Hey, I’m actually doing this.’ And you are.”

copyright © 2005 Port Folio Weekly. Used by Permission.