“Downtown, where all the lights are bright…”

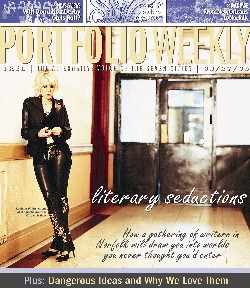

The voice on the other end of the line singing Petula Clark’s 1964 pop hit was that of Lucinda Williams. Though she’s known for her intense, autobiographical blend of folk, country and rock, she’s also a fan of the pop fluff of her youth.

“There’s nothing wrong with a great pop song,” she told me last week. “That’s an art unto itself, to write a great pop song, that’s a whole ‘nother thing. That’s why they used to have good songwriters back in the day like Burt Bacharach. I love all that stuff. [Singing] ‘What’s it all about, Alfie,’ ‘Chances are…’ Those are really well written songs, great chord changes, but also they’re really underestimated in terms of their lyrical structure.

“I continue to learn all the time from different styles of songwriting. But basically I do what I do because that’s all I know how to do.”

She knows how to do what she does very well, and has three Grammy awards in three different music genres to show for it---Country Song of the Year for “Passionate Kisses” in 1993; Best Contemporary Folk Album of 1998 for Car Wheels on a Gravel Road; and Best Female Rock Vocal of 2001 for “Get Right With God” from her album, Essence. She comes to Norfolk next Friday, October 7th, to wrap up the ODU Literary Festival at the Granby Theater with her father, renowned poet Miller Williams.

She knows how to do what she does very well, and has three Grammy awards in three different music genres to show for it---Country Song of the Year for “Passionate Kisses” in 1993; Best Contemporary Folk Album of 1998 for Car Wheels on a Gravel Road; and Best Female Rock Vocal of 2001 for “Get Right With God” from her album, Essence. She comes to Norfolk next Friday, October 7th, to wrap up the ODU Literary Festival at the Granby Theater with her father, renowned poet Miller Williams.

Dad was also a college professor, so Lucinda grew up surrounded by college students, educators, poets and writing friends of his. It was an exciting time on campus, the fervent, freewheeling atmosphere of the ‘60s.

“I can remember sitting up nights back in Fayetteville with some of his writing students,” she said, “hearing them debate back and forth as to whether Bob Dylan was a poet or a songwriter, and whether Leonard Cohen was a poet or a songwriter. I was very fortunate because I was able to be exposed to some songwriters that may have taken me longer to discover.

“I remember back when he was teaching at Loyola. I was a teenager and I can remember some of his writing and poetry students coming over to the house. In fact, that’s how I first discovered Bob Dylan---We were living in Baton Rouge in 1965 and one of his poetry students came over to the house one day with a copy of Highway 61 Revisited, and was just raving about it, saying ‘you have to hear this record, you have to hear this record!’ And I grabbed it.

“They ended up sitting down and talking about something else. So I started playing it and listening to it. And it just completely blew me away and had such a profound impact on me at that young age of twelve-and-a-half. I wasn’t exactly sure what all the songs meant, but I knew that I had discovered someone who had brought the two worlds together that I was also from, which was the world of folk music and country music and mountain music, and the world of poetry. And here was someone who had managed to take both worlds and connect them. It just completely mesmerized me, and I was hooked from then on.

“That really set the stage for me, as far as what I wanted to accomplish as a writer and an artist. I had started out listening to all the traditional folk music, then some of the contemporary songwriters and singers like Gordon Lightfoot and Buffy Sainte-Marie. I hadn’t heard his records before; that was the first one I had heard. So that whole folk rock thing I just really connected in with.

“And then later I got turned on in the same fashion to Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell when we were living in New Orleans. Again, his students would come over to the house and bring those records over. But my dad wasn’t really interested in any of those artists. He was listening to Hank Williams and Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette and John Coltrane and Chet Baker. So I was exposed to all of that great stuff.”

-

Her parents separated when she was twelve and her father got custody of the children, but she stayed close with her mother as well:

“We all stayed connected to each other. We were living in Baton Rouge at that time, and then later we moved to New Orleans. My mother also lived in New Orleans. When we ended up in Fayetteville in ’71 [at the University of Arkansas], she stayed in New Orleans. So I would go visit her down there whenever I could. In fact, during one of those visits to New Orleans, I got offered a job playing at this little place called Andy’s on Bourbon Street in the Quarter. It was my first sort-of paying gig; I played for tips I think. But I got offered a regular thing there a few nights a week. So I called my dad because I was supposed to be going back to school in the fall---this was in the summer of ’72. And he said, ‘Well, you can always go to school later. If that’s what you want to do, go ahead.’ So that was one of those major turning points. I had a lot of creative freedom when I was growing up.

“I was going to major in cultural anthropology, or so I thought. I think that came from traveling a lot. We had lived in Santiago, Chile, for a year in ’63, and then we lived in Mexico City for a year in 1970. So I was really inspired by the Latin American and Mexican culture, all this great folk art and the music too.”

Instead of going back to college, she went to Austin, Texas, in 1974, arriving just as the music scene there was taking off. She spent most of the next ten years honing her craft and performing, moving between Austin and Houston with a brief period spent living in New York City just before her first album, Ramblin’ on My Mind, was released by Folkways in 1979. She wound up in Los Angeles in 1984.

“By the time I got out to L. A.,” she recalled, “and I was getting known by record company people, I just kind of fell into the cracks between country and rock. They didn’t know what to do with me. That whole alternative music market hadn’t even started, or the industry hadn’t recognized it as such. I was kind of at the beginning of all that stuff.”

But she stuck with it, gradually growing her audience and building a resume full of positive reviews and critical notice. Mary Chapin Carpenter’s hit version of “Passionate Kisses” upped the ante in the early ‘90s, and in 1998, she released her south-specific, autobiography-drenched masterpiece, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road. Since then, her songwriting has gotten more precise, her music even more satisfying. In 2001, Time magazine named her “America’s Best Songwriter.” When she called me from Santa Fe, New Mexico, she was in the final weeks of a four-month tour in support of her latest album, the double-disc Live @ the Fillmore. Through it all, she has plumbed her own life and experiences for lyrical inspiration.

“I create first for myself, because that‘s what art is about,” she explained, “it’s self-creation and self-expression. So I write first for myself, because I’m writing from a journalistic point of view, a journalistic style of songwriting I guess. I’ve never really called it that before, but I guess that’s what it is. Then I want to get it across to other people. That’s sort of the second stage. I think one works with the other.”

She’s looking forward to the joint performance here with her dad. I asked her about his poem, “The Caterpillar,” one of his best known poems. He had told me he got the last lines from her when she was five years old.

“It always makes me cry,” she said. “You know, kids come up with amazing lines all the time. It’s just a matter of taking advantage of the situation as an observer, which is what being a writer is all about---observing a little story that’s probably been repeated in countless numbers of households throughout history. It’s awesome---that’s the beauty of his writing, that he’s able to observe something like that and turn it into a great piece of poetry.

“He’s a great writer. One of the many important things I learned from him is not to be an elitist when it comes to your art. He taught me a lot about that. You want it to be understood. There’s not much point in creating a piece of art if you’re the only one who knows what it means.”

copyright © 2005 Jim Newsom. All Rights Reserved