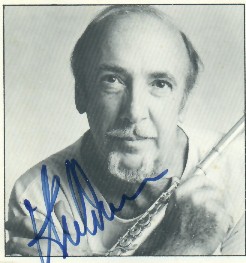

Herbie Mann talks a lot about "the groove." One of the most commercially successful jazzmen of the last half-century, the 72-year old flutist has spent his lengthy career searching for, and usually finding, "the groove."

In the 1950s, he found it, along with initial success, in Afro-Cuban and Latin music. He subsequently locked into a Brazilian groove in the early '60s, then moved into a funky, soulful groove in the late '60s and early '70s. By the mid-'70s he was making hit disco records, still cooking in a rhythmic groove.

Nowadays, however, Herbie Mann is working in a new and different kind of groove. Diagnosed in November of 1997 with inoperable prostate cancer, he has become a crusader for prostate cancer awareness. Fighting his own battle against the disease, he has formed the Herbie Mann Prostate Cancer Awareness Music Foundation in the hope of saving others from the pain and radical treatments he himself has undergone.

I spoke with Herbie Mann recently at his home in New Mexico for Port Folio Weekly about his musical journey, his cancer, and his crusade. We had a wide ranging discussion, appropriate for a performer with such an eclectic catalog of recordings.

"When Mat Matthews gave me the opportunity to record jazz on flute in 1952," he said, "there was no tradition of straightahead jazz on the flute. There was Wayman Carver with the Chick Webb band, Harry Klee in Hollywood, and Sam Most. That was it. To many listeners and to most musicians, the flute wasn't a jazz instrument.

"So, when Symphony Sid, the DJ in New York, suggested I add conga drums because he was a mambo-nick, all of a sudden the audience understood where the flute was. It was jazz, but it was Latin jazz. In Latin bands, the flute was one of the solo instruments. It had always been the case."

The addition of conga players brought him his first taste of popularity in 1958. "I had a band with four drummers," he noted. "I thought four drummers would kill the audience, which it did. But then I became a sideman in my own band. Musically, it started getting very generic. The Latin music was basically a two-chord tune. After a while, it started driving me crazy."

The addition of conga players brought him his first taste of popularity in 1958. "I had a band with four drummers," he noted. "I thought four drummers would kill the audience, which it did. But then I became a sideman in my own band. Musically, it started getting very generic. The Latin music was basically a two-chord tune. After a while, it started driving me crazy."

A 1961 tour of Brazil changed his life.

"I figured that it all came from different parts of Africa," Mann says, "so maybe Brazilian music would be my salvation. And it was. It not only had the rhythmic excitement, for the first time I heard beautiful melodies that were great to improvise against."

He became the first American musician to record Brazilian music in Brazil with Brazilian musicians. In the bossa nova-crazed days of the pre-Beatles early '60s, Herbie Mann emerged as one of the most popular performers in jazz. He was making world music long before that was a recognized musical genre. He took the diverse rhythmic influences of his multinational band lineup and mixed them with the blues to produce his first big hit, "Comin' Home Baby," on the Herbie Mann at the Village Gate LP in 1962.

But Mann has never been content to stand still, and the fertile musical environment of the 1960s offered a great deal of inspiration to a musician with open ears and an open mind.

"It became quite simple for me to go and look at different parts of the world. Every civilization had flute in their music, except American."

But it dawned on him that there was a rich, ethnic music right here at home---soul music, rhythm and blues. And he decided to place his flute in the midst of it.

"I realized that in order to play a specific music, you had to go where the sauce was. I'm not going to do an album where I want real authentic Brazilian rhythms and record it in Jamaica. If I go to Brazil to make a Brazilian record, if I use Latin players to make a Latin record, why don't I go to the place where it's natural for those players to play that groove? So I went to Memphis. I went to Muscle Shoals."

And the results were hugely successful, especially the 1969 album Memphis Underground. Subsequent recordings such as Muscle Shoals Nitty Gritty, Mississippi Gambler and Push Push continued the string of funky groove-oriented albums.

He formulates his approach succinctly: "All you have to do is find the waves that are comfortable to float on top of."

However, commercial success comes with a price in the jazz world. When Herbie went disco in the mid-'70s, the critics were not kind. His audience shifted as well.

"It's a double-edged sword having some pop records like 'Hi-Jack' and 'Superman' out there," he said. "Pop is a very temporary pinnacle. You can go from having a Top Ten seller to not having anything. In the jazz market, even in the broadest sense, you normally carry your fans along your whole career until they start dying out."

Commercial success gave him the opportunity to work with, and produce records for, other artists he admired. Pulling from his own working band, he was the first to produce Chick Corea, Roy Ayers, Sonny Sharrock and Miroslav Vitous.

It also gave him the freedom to say "no."

"One of the things I did not do, because I really do not feel rhythmically excited about it, is smooth jazz or fusion. I had that choice. The head of Atlantic Records asked me if I'd like to do a record produced by the Crusaders. I said 'no.'

"Growing up where rhythm is the heartbeat of the music, to me the bass player is the heart of the rhythm. With fusion, the bass player's role changed, it stopped being rhythmic and started being melodic. For me, the music stopped grooving.

"Listen to Memphis Underground or Push Push. That's the epitome of a groove record. The rhythm section locked all in one perception. Fusion music didn't have that unconscious groove. For lack of a better definition, the groove stopped being reefer and started being cocaine."

Since leaving Atlantic Records at the end of his commercial heyday in 1979, Herbie Mann has continued to tour and record. (He headlined Norfolk's Town Point Jazz Festival in 1984 and 1988.) But the pace is different. After averaging two or more albums a year in the '60s and '70s, he's released eight recordings in the last twenty-one years. He moved to New Mexico from New York with his wife Janeal in 1989. But he's continued his musical search for the groove.

1995 was an especially productive year for the flute man. That spring he recorded what is perhaps his finest album, Peace Pieces, a tribute to pianist Bill Evans, with whom he'd recorded thirty years earlier. He also produced a weeklong series of concerts at the Blue Note in New York City to celebrate his sixty-fifth birthday, out of which he culled two excellent discs, Celebration and America/Brasil.

After being diagnosed with inoperable cancer, he began looking in a different direction for inspiration.

"When that happens, you immediately start thinking that it's the end of your life," he explained. "What do you want to be remembered for. And it dawned on me that I've played music I loved all my life, but they've all been assimilations. I'm not Brazilian, I'm not black, I'm not Jamaican---I'm a second generation Eastern European Jew. So why don't I look at that music and see if there's anything in there I can use."

"When that happens, you immediately start thinking that it's the end of your life," he explained. "What do you want to be remembered for. And it dawned on me that I've played music I loved all my life, but they've all been assimilations. I'm not Brazilian, I'm not black, I'm not Jamaican---I'm a second generation Eastern European Jew. So why don't I look at that music and see if there's anything in there I can use."

So he started listening to the music of his own ethnic heritage. He met some of the musicians, formed a new group called Sona Terra that includes his son Geoff on drums, and began exploring another musical groove. The initial results can be found in his most recent CD release, Eastern European Roots, which he originally put out on his own label and sold over the internet and at concerts. It has just been issued by the nationally distributed Lightyear Entertainment label.

His plans include a trip to Hungary to record with Hungarian musicians.

"All of these guys grew up under Communism," he remarked. "They had to secretly listen to the Voice of America. Now they are using this knowledge to play their own harmonies and rhythms based on their folk music. It's a totally different genre. This music gives me the same kind of goosebumps like the first time I heard Benny Goodman, Lester Young, Charlie Parker…and Brazil."

When I spoke with Mann in May, his plans were to make that trip in June. However, the prostate cancer got in the way. He developed blood clots in his lungs, and had to postpone the European trip until the fall.

His cancer had been in remission for two years, but his PSA level went up to 70 a few months ago. (See accompanying interview with Paul Schellhammer, MD, for more on PSA levels.)

"I'm going to start some new treatments," he said. "I've done radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy. We're talking about a median prognosis of two to five years, but I don't accept that. I'm starting a regimen that will include bone defense chemo and then some radiation and pills."

The Mann family is personally fighting the cancer battle on two fronts: "My wife Janeal had a lumpectomy. They had to remove twenty-one lymph nodes and one had a tumor. So, she's starting a four-month regimen of chemotherapy. She's stage two, so her prognosis is not the best but it's not the worst."

And through education and information, the couple are trying to save others from the kind of ordeal Herbie has endured.

"My foundation raises money to do concerts. We have onsite PSA blood tests for free. Everybody that gets a blood test gets a free CD."

He encourages men to get their PSA level checked.

"If you are connected to any other human being," he says, "it's your responsibility to take care of yourself for them."

Herbie Mann's music continues to inspire and entertain. There are currently more than fifty of his albums in print, from all the different stages of his career. And now, he hopes to use his celebrity and his music to inspire and inform others about the importance of early cancer detection. In his case, by the time his cancer was discovered, it had spread beyond the prostate gland, and thus was inoperable. He hopes to help keep others out of the same predicament.

He sums it up with this message on the Herbie Mann Prostate Cancer Awareness Music Foundation website: "I would not have had to have endured such radical treatment if I had known about the PSA---if I had been armed with the information that would have detected the disease before it had spread. This knowledge would have dramatically altered the course of my life."